perstekst:

Antwerpen, 24 september 2010

In Square 1 toont Narcisse Tordoir een reeks tekeningen, twee schilderijen, een video en een krant. De werken suggereren samen het bestaan van een oversized-sacraal schilderij dat niet te zien is. Het bestaat wel degelijk, maar wacht op een andere locatie in de stad om getoond te worden. Square 1 gaat, als in een spel, terug naar af. In een soort van time collapse duwen de werken de antropoloog, de socioloog en elke andere toeschouwer met hun neus op de feiten: of die feiten nu van vandaag of van 20000 jaar geleden dateren, wat er tussen mensen gebeurt kan alleen maar bekeken, interactief geïnterpreteerd en nooit ‘van op afstand’ ondubbelzinnig begrepen worden. En dit niet omdat we er ‘niet bij waren’, maar net omdat we erbij horen. De mens regisseert zijn rituelen en registreert ze in beelden. Die beelden zijn vandaag gepolijst, getrukeerd en gesofistikeerd, en neigen in hun populaire gemediatiseerde vorm weg te kijken van de geweldloze sacred horror die de mens ‘bovennatuurlijk’ nodig heeft. Square 1 toont dat er sinds het ontstaan van de mens wat betreft het ritueel van de liefde, sex en de dood niets veranderd is, maar ook dat het maken van kunst-beelden een essentieel onderdeel van dat ritueel is. De epiloog van de show is visuele leegte, bevrucht en besmet door wat vooraf ging, en dus klaar om opnieuw ingevuld te worden. (tekst : Gaston Meskens)

Text as it appeared in the publication of the show:

Wonderment is Cool (Cave Painting Today)

In “Square 1”, Narcisse Tordoir shows a series of drawings, photos and paintings, a video and a newspaper. Together, the works suggest the existence of an oversized sacral painting that is not on view in the gallery. It does exist, but it waits to be shown at another location in town. Although not displayed at the ‘principle’ public location, the work is not downgraded or dislocated. The official pragmatic reason for the fact that it is not shown there is that its dimensions surpass those of the gallery. The real motive for its erection at an off-peak location is different however: the painting is on view in the deepest, almost inaccessible part of the cave.

Stumbling into progress (a short story of humanity)

The development of consciousness and the talent of intelligent reflection made the human to live in a default a priori mode of wonderment. In this development, which is, as it is said, what distinguishes humans from other living creatures, wonderment manifests in three ways, being

1 / The awe for what is ‘outside’: the natural environment, its meaning and its origin;

2 / The puzzlement with respect to what is ‘inside’: the self, and its relation to the body and, based on the consciousness about the distinction between life and death, the subsequent fear for the death;

3 / The struggle to make ourselves understandable in interaction with the other, about this awe, this puzzlement and this fear, and about our relation to this other (with his awe, puzzlement and fear).

But despite of the oppressive character of these stances of wonderment, and despite of the growing consciousness of the complexity of it all, the early human being, who separated himself from the animals on the basis of his reflective capacities, had no time to sit back and reflect on the origin and meaning of nature and life or on more deliberate aesthetical or ethical modes of human interaction. Bare necessities needed to be met, and in the interest of this, man hunted, gathered and travelled, leaving one exhausted area for another promising place. Meanwhile, fear, awe and puzzlement were relieved through escape into unhierarchical collective rituals. With the change from nomadism to the living mode of settlement in self-sustaining agricultural communities, the practice of economic trade and the overall need for social functional organisation emerged. The structures of social organisation provided the incentives for the development of organised religion and science. These ways of making sense of the world apparently finally provided a cure for the human angst, as, in various parallel phases of civilisation, they both attempted to rationalise the stances of wonderment into big stories of belief or evidence of proof. Rituals became politicised and knowledge became a source of power.

And finally, out of the need for functional social organisation, the idea of social inclusion materialised easily, as it was only a matter of coupling the concept of social identity to a geographically demarcated living space. By keeping the group together, generation after generation, social identity gradually motivated social inclusion and vice-versa. But in this model of demarcated self-sustaining communities, the included became unavoidably occupied with conflict, intra muros with power struggles and extra muros with pillaging or defence against it (as it seemed easier to conquer another communities’ stock than to build up an own). The idea that safeguarding social identity is a bare human necessity was born, and all existing communities, identified by differentiation, agreed that this safeguarding should be done through protective inclusion and conflict and defensive exclusion and threat, and all of them shared the conviction that this approach, although regrettable, is an unavoidable aspect of the spirit of humanity.

And since then, nothing essentially changed.

That is: nothing changed about how humans think living modes should be organised and rationalised. Since the enlightenment, and especially during the last century, critical thinking and shocking war experiences challenged the beliefs in eternal spirits and empirical evidences, and technological progress brought global benefits and global problems. The bare plain in between the distinct gated communities has long been crossed and filled, and we all live now inside each others territories. The original idea of the community that, on the basis of the abstract notion of ‘inclusion by identity’, attempts to be self-sustaining through intercommunal trade and political protection is not longer relevant, and instead of realising that ‘inclusion by identity’ is a false approach that can easily be misused in oppressive power structures, we still try to solve our now globalised problems through this outmoded socio-political model. And still there seems to be no reason to critically but compassionately reflect on human wonderment, as still, fear, awe and puzzlement are relieved through collective rituals. They seem to be unhierarchical, as in their contemporary form, all humans have the freedom and right to buy the same products, spend their holidays in the same places and watch the same TV channels. The freedom and right is mediated and thus false, but most don’t care. They have no time to care, as bare necessities need to be met.

The unrecognised aesthetics of resignation

In September 1940, the paintings in the cave complex of Lascaux inFrancewere discovered. Although cave paintings were found in other places already, anthropologists were stupefied by the abundance of depicted scenes, the level of detail of the figures and the vivid colours used in this case. It became soon clear these works were about 17000 years old. They were created during theUpper Palaeolithicage and had been sealed of from the outside environment since then. The awe for the beauty of the complex was (and still is) accompanied with curiosity about the what and why of the depicted scenes, but also with a feeling of resignation, as we realise we have very little elements of knowledge to reconstruct and understand what the scenes represent. What is known is that, during that time, the Homo Sapiens coexisted with the Neanderthal man. Both are now considered as ‘human’ – in the sense of ‘different from animals’ – because they were both conscious of the difference between life and death. The burial rituals that can be reconstructed from archaeological findings show that these early human creatures, unlike animals, were terrified when faced with death. The rituals, including the offerings, were nonviolent and may be understood as a sign of respect for the deceased, but also as an attempt to protect the survivors against the mysterious power that took their tribe member away. The traveller-hunter-gatherer was a conscious but resigned and accepting human. He had no sense of the potential of settling in social organisation, but consequently also no sense of the threat of human conflict.

But a resigned consciousness affects the ways of expressing moods and impressions, and this has consequences. One essential thing distinguished the Homo Sapiens and the Neanderthal man: so far, our knowledge learns us that the Neanderthal man did not make art. Cave painting and sculpture are a typical thing of the Homo Sapiens, and in doing this, his genius separated him from the soon-to-be-extincted Neanderthal man. His genius is human in the sense of unnatural, as the art drawings may be seen as acts from out of pure wonderment, disinterested in the sense that they had no direct instrumental function in the daily struggle for survival. But immediately these drawings showed their magic power, as they provided a mean for these humans to express their fear, awe and puzzlement, either by making the drawings or by looking at them. One particular scene in the Lascaux cave suggests this in a unique but mysterious way. In the deepest, almost inaccessible part of the cave, a man with a bird-like head faces a bison in a hunting scene. While the man is drawn in clear but very rudimentary line, the animal is depicted with a high level of detail and colour use. Many interpretations have been made of this scene, but the one formulated by Georges Bataille in The Cradle of Humanity is interesting. He suggests both figures are dying, in front of each other, as in a mutual nonviolent sacrifice of complementary deaths: “…But this man at the heart of the cave’s recesses did not assume the proud and particularly personal heroism that is peculiar to modern times. He did not slip into this individual vanity that humanity perhaps found in war. … From the depths of this fascinating cave, the anonymous, effaced artists of Lascaux invite us to remember a time when human beings only wanted superiority over death.”

Long before science and organised religion aimed to present a rational case for wonderment, art provided a first innocent mean to make sense of it. The cave artist, as the magician, joined the technician (who provided weapons for the hunt) in being the first human intellectuals. Both had a different role, but, more important, both had no strategy. In expressing religious and erotic ‘moods’, the early human artists were innocent. Their innocence was genuine, but not deliberate. It could not be deliberate, as they were ‘first’, and they had no choice. But their unchosen intelligent-emancipating stance reminds us today that pure religion and eroticism, even in their most decadent forms, are unselfish and disinterested. As soon as humans imply them into a power structure, they become cruel. Cruelty, even in passive form, does not come with intelligent idleness, but with the stupidity of selfishness. The human being is not cruel by default, but innocent. But, in contradiction to cruelty, innocence brings along responsibility. And that is a hard burden to carry.

Civilisation, in the sense of streamlining human organisation into conformist patterns, self-rationalised on the basis of ‘natural’ tradition, organised religion and, recently, social sciences, is a therapy that focuses on the wrong disease. That is, it assumes human reflective wonderment is the disease that should be cured, instead of accepting it as that what makes us human. Wonderment is cool, and awe, puzzlement and fear are intelligent states of being, even so the melancholy that comes with the consciousness of all this. Human disinterested reflective wonderment is about curiously accepting limits to the knowable. But the modern human considers these limits as a temporary and intermediate phase in the linear process of human progress. Since the ‘enlightenment of the ratio’ and up till today, humanity did not accept yet that human natural, social, economical, scientific and political interactions are complicated by degrees of uncertainty, ambiguity and complexity that ‘by design’ cannot be cleared out. This denial, supported by as well postmodern relativists as (neo)conservative truth-seekers, has led to a general phobia for the unknown that gives way to all kinds of strategic rationalisations and simplifications in the social and political sphere. Today, ‘innovation’, in a thin understanding, aims to develop the technological human, but forgets to take along the philosophical human first. The reason is not that the latter would be too difficult to treat, but rather that it requires solidarity and, above all, engaged cultural relativism.

With our contemporary gaze blinded by the behold of today’s fictional and factional scenes of complacency, mediocrity and violence, and our mind and memory contaminated with the wearisome stories behind, are we still capable of grasping the essence of man’s first art works?

I claim the answer is no, but it doesn’t matter, as innocence can be reinvented. It can be reinvented in science and religion driven by disinterested curiosity and belief, and in art driven by disinterested empathy. But art is the only way of making sense that, at the same time, can be meaningfully conceptual-ironic, conceptual-decadent and conceptual-aesthetic. It makes sense because it takes wonderment serious while acknowledging it cannot provide answers. The short story of humanity, as told in the first part, was obviously incomplete, as art was not mentioned.Lascauxreminded us that art is the ultimate medium to make sense of wonderment, as it is the only way of making sense that provides a cure for wonderment without treating it as a disease.

Narcisse Tordoir’s compassionate research in the visual arts

From today’s perspective, the contemporary art world would call theLascauxpaintings outsider art. Outsider art is that kind of visual art that, according to the included, ‘misses the point’. That point is the point of no return: since the emergence of modern art, and especially of conceptual art, visual art always ‘conceptually’ shows/suggest/tells more (or less) than what is visually detectable. As a deliberate act, this performance can be regarded as a new achievement in the human intellectual programme of ‘compassionate but unstrategic making sense of wonderment’. It may be that we do not understand yet what conceptual art is.

It is senseless to judge whether the early Homo Sapiens missed the point or not. His work may have been conceptual too, and we will never know. This is one message of Square 1. The show goes back, back to where we belong. In a time collapse, the works face the facts: whether these facts date of today or of 17000 years ago, what happens in between people can only be observed and interactively interpreted, but never objectively understood ‘from a distance’. The reason is not that we were not part of the game that time, but simply because we are always part of the game. The human being directs his rituals and captures them in images. Today those images are polished, tricked and sophisticated and in their popular-mediated form they tend to look away from the nonviolent supernatural sacred horror the human being is craving for.

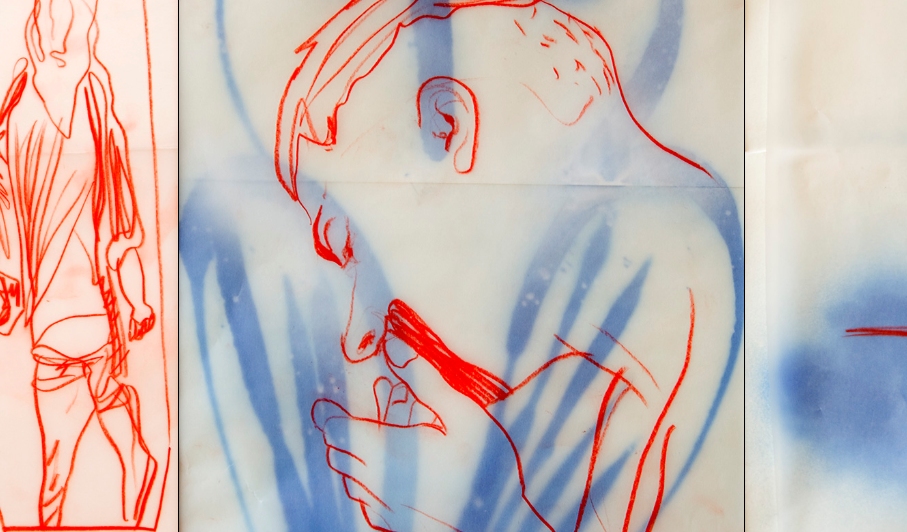

Square 1 is conceptual in its innocence. The work is innocent, but obviously not naïve. It is not naïve because the deliberate intelligence emerges from the process the physical works have undergone. They are the remainings of a double re-enactment. The first is a replay of theLascauxscene mentioned above. The rudimentary man is now split into a diverse group of actors, while the diverse group of animals is collapsed into one rudimentary animal-like sculpture. The actors adopt a pose of disinterest. In their helplessness and mannerist unstrategic poses, they are supported by an animal that seems to be nothing more than a wooden frame and a pathetic Disney-style face. The animal can’t help, and neither can the actors, because, compared to the figures in theLascauxcave, they are now conscious of what happened to nature and humanity meanwhile. The mask of the suicide terrorist is actually the mask of a sadomasochist, not of a self-proclaimed or mislead hero. The re-enactment of the happening is only half of the work. Narciss Tordoir also ‘re-paints’ the painting of the scene. The paintings and drawings on view suggest they have already been painted once before. For Narcisse Tordoir, painting is an instrument to create an image of painting.

Square 1 is a compassionate-ironic ode to the nonviolent, to the nonviolent supremacy of human wonderment in its manifestations of fear for the death, puzzlement about the self and awe for nature and the other. The works show that since early humanity nothing has changed in the ritual of love, sex and death, but also that the creation of art-images is an essential part of those rituals. The epilogue of the show is visual emptiness, fertilised and contaminated by what preceded, and thus ready to be re-enacted, again.